The Earth is flat, don’t you know? Aliens are real, haven’t you heard? The government killed JFK, right?

People all over the nation believe in these conspiracy theories, but in order to gauge why people may believe the Earth is flat, it is critical to understand what’s going through their brains while they learn about a conspiracy theory.

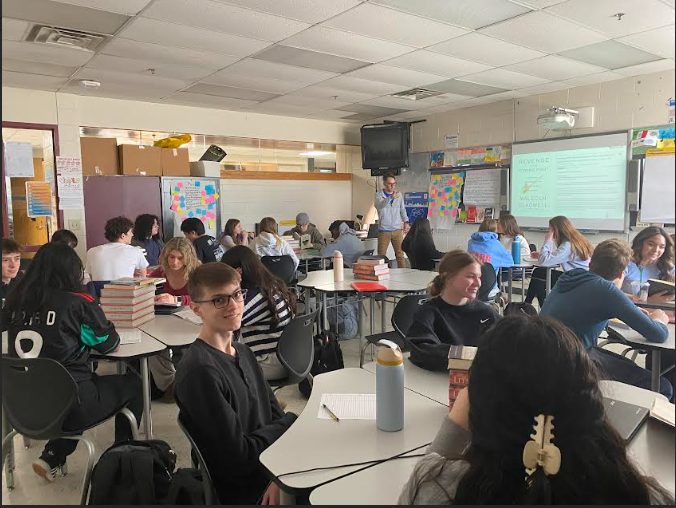

Social Studies and AP Psychology teacher, Melissa Schaefer, defined a conspiracy theory as “an idea that somebody believes that they think is true with little to no evidence. It is an explanation for some sort of behavior or some sort of circumstance, usually negative in nature,” Schaefer said.

Another AP Psychology teacher, Dean Petros, added that “a conspiracy theory is when a person thinks that something happened, and it was due to some hidden motive. I think of a person who feels that the full truth isn’t being told, that something’s being hidden.” Therefore conspiracy theories often result in an increase of paranoia.

However paranoia is not the only disorder that aligns with conspiracy theorists. “I’m guessing people who have a propensity to believe in conspiracy theories have high anxiety, neuroticism, fear, paranoia, and paranoia tendencies,” Schaefer said. Additionally, Petros added how conspiracy theorists will typically display signs of OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder, causing them to constantly think and research about the conspiracy theory. The conspiracy becomes an important belief in their life.

The action of believing in a conspiracy theory takes part in a specific area of the brain known as the prefrontal cortex, according to Schaefer. Additionally, “your decision making, judgment, and hypothetical thinking comes from the prefrontal cortex (which is the front part of the frontal lobe). However, because judgment involves the memory of things, the hippocampus is also involved,” Schaefer said.

On top of the biological components that influence the brain when listening to/believing in a conspiracy theory, social aspects also play a part.

The article “Speaking of Psychology: Why people believe in conspiracy theories, with Karen Douglas, PhD,” by the American Psychology Association (APA) explains how there are three things that motivate people to believe in conspiracy theories: epistemic, existential, and social motives.

According to Karen Douglas, “Epistemic motives really just refer to the need for knowledge and certainty and I guess the motive or desire to have information. The second set of motives, we would call existential motives. And really they just refer to people’s needs to be or to feel safe and secure in the world that they live in. The final set of motives we would call social motives and those refer to people’s desire to feel good about themselves as individuals and also feel good about themselves in terms of the groups that they belong to.”

Petros added, “The psychology behind conspiracy theories “[extends] beyond biology. There’s cognitive patterns like confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is when people will seek out information that confirms whatever biases they have. We find a lot of research [suggesting] that when people go online, they tend to go to the same few sites. Typical conspiracy theories will only go to websites or listen to podcasts by people who have similar thought processes of the world and similar views of that conspiracy theory.”

Technology certainly plays a role in confirmation bias. Schaefer added, “For instance, my phone or my device is listening and knows that I have a dislike of celebrities–from any number of either searches I’ve done or things I’ve looked up. My phone already knows what I believe, and then it shows me things that align with that belief. On top of that, because of the way the internet works through algorithms, I’m not shown anything in the opposition.”

Both Petros and Schaefer agreed that it can be dangerous when people are never shown opposing opinions. This can lead “people to develop this idea of belief perseverance,” Schaefer said, “once you’ve developed a belief and you feel strongly about it, then it is incredibly hard for people to change it even when they’re given evidence that doesn’t support it.”

Petros explained that while people may have a positive bias towards people who think and act similarly to them, they may have a negative bias towards people who are different from them. It becomes dangerous when a person makes a generalization about all people who are different from them, Petros added. Petros further explained how this may result in some of the prejudice behaviors that we have today in our society.

In order to prevent the harmful effects of believing in a conspiracy theory such as confirmation bias and belief perseverance, both Petros and Schaefer stressed the importance of finding reliable sources when conducting research.

Petros said that while there are plenty of research-based sources that are reliable on the internet, people need to be vigilant for sources that may spread false information, especially with the increased usage of Artificial Intelligence recently. “AI can have computers that make fake videos. You’ll see people in a video and it’s not the real person. It’s almost like you have to distrust what you see,” Petros added.

Schaefer mentioned the importance of using multiple sources, including ones that include the opposing argument. “Even if you to want believe a conspiracy, you have to spend the time looking at what other people who don’t believe it are saying or the counter-evidence because there’s a lot with technology that we have access to; there’s a lot of ways to make things that are not real seem real,” she said.

However, believing in conspiracy theories is only harmful if it “interferes with logical thinking,” as Petros said. There’s a difference between having fun believing in a conspiracy theory and then actually being a conspiracy theorist.

Schaefer said, “I think for some people it is just fun–the idea of something kind of crazy or wild being possible. For instance, UFOs, [stimulate] intrigue or fantasy. [People] find them very fascinating. I don’t know that there’s anything wrong with that line of thinking either. It’s natural for humans to want to explain things. Our brain naturally likes to have causes and effects.”

Schaefer also described illusory correlations–when people believe that something has an effect on an outcome when it really doesn’t. She said that the brain likes to use illusory correlations in order to justify an effect.

The next time you come across someone who strongly believes in a conspiracy theory, take a minute to think about what’s going through their head, for it truly does require psychology to understand why people believe in the things they do.