MHS Committee Considers Later School Start Time

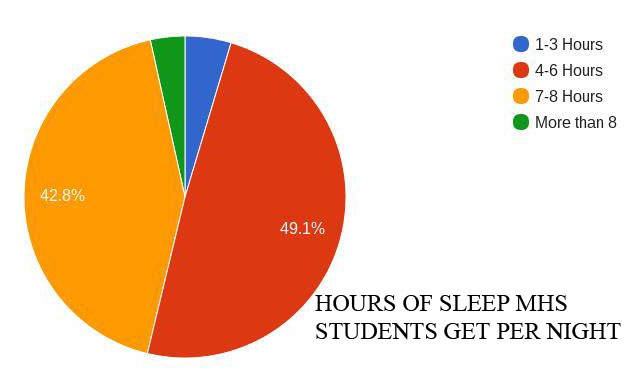

In a survey of 200 students, 49.1% only get between 4 and 6 hours of sleep.

December 17, 2015

While walking through the hall, one may see black rings under the eyes of students and teachers before the first period bell. Focus can be low, and some students might struggle to stay awake during class. This may all result from a start time of 7:45 a.m.

As a result, MHS has formed a bell schedule committee to not only consider the pros and cons of the block schedule but also to review the potential of starting at a later time.

According to Tom Buenik, Director of Guidance, the school administration is already considering a later start time by looking into the costs and the schedule adjustments needed. A change to the schedule could be as soon as the 2017-18 school year.

Stevenson High School has already declared school-board-approved changes for the 2016-2017 school on its website. One of those changes includes “every school day [starting] 25 minutes later, at 8:30 a.m.”

“About 8:30-8:40 a.m. should be the earliest. It would be even better to start at about 9:20-9:30 a.m.,” said Dean Petros, psychology teacher, in an email.

Petros cited a case in Minneapolis in which the school districts saw academic growth when about a decade ago the start time was pushed back to 8:40 a.m. with a 3:20 p.m. release time.

“The average SAT score went up 100 points,” he said. “If the writing portion isn’t included, this is the equivalent of a 2.5 point improvement on the ACT.”

According to Illinois legal aid, students in Illinois can have as little as a five-hour school day.

MHS currently has a seven-hour-35-minute day, which results in six hours and 30 minutes of classroom time, including homeroom. However, seniors with a free period have fewer classroom hours.

Therefore, state requirements could still be met if the representatives on the bell schedule committee – which is comprised of two teachers from each department and about five school administrators –recommended a 9 a.m. start time with a 3:30 p.m. release.

Several teachers support the idea of a later start time, including bell schedule committee member and English teacher Jim Drier.

“I think that having students here at 7:45 is immoral,” he said.

He added, “My students have no life [at that time]. It’s not that they’re asleep; it’s that their brains are not functioning. The difference between first and second is dramatic.”

He said that students in his second period class compared to his first are much more alert, focused, engaged and inquisitive, as it goes with every second period class when compared to a first period class that starts at 7:45.

What Drier is noticing might be because “the ability to focus and block out distractions is impeded with sleep deprivation,” according to Petros.

He added that a lack of focus with sleep deprivation creates an environment that through no fault of the teachers encumbers learning.

Consequently, a later start time might help students become more involved in their classes.

“There is a significant body of research that shows that sleep loss hurts your ability to focus,” said Petros. “Research conducted at the University of Pennsylvania demonstrates that it is a cumulative effect. One night of only four hours of sleep hurts your ability to focus; a second night is worse; a third night is even worse.”

And many students report not getting the suggested hours of sleep.

For instance, Junior Shane Kosmach wakes up at 5:30 a.m. and falls asleep usually around 11 p.m. This is three-and-a-half hours fewer than what is recommended for teens his age.

“Students should get approximately eight-and-a-half hours per night. This can only occur if the starting time of the day was pushed to approximately 9:20-9:30 a.m.,” Petros added.

While some might argue that students should just go to bed earlier, Petros explained that the brain doesn’t make a person feel tired until about 11 or 11:30 at night, and this is without the light of Chromebooks and phones, which can trick brains into thinking it’s earlier than it actually is, causing people to fall asleep even later.

The feeling of restfulness is little better for teachers.

“I’m exhausted,” said Drier, who wakes up at 4:30 a.m. each day and falls asleep around 9:30 each night. “It takes a ton of emotional energy to manage a classroom full of students. And if you’re a student, you can sit in class, and you can space out…. Teachers can’t do that. We have to be on 90 minutes straight, and you need to be hyper vigilant.”

If the schedule were changed, one area that might be affected is homeroom—it may no longer exist.

While many would like to see homeroom go, it has been put into place for specific reasons.

According to Buenik, the school included homeroom because it offered a 30-minute block in the day to be used as a home-base for announcements, a study hall and a time for students to get help from teachers.

It also allowed seniors to have a free period so that they met the required state law of being in class for 300 minutes a day.

An additional change might include class periods that are no longer 90 minutes.

Shorter class periods over a longer time period have its positives.

Each day’s lessons would be shorter, and therefore, the student would not miss as much information if he or she were absent from an illness.

As Drier said, “If [students] miss a day in [this current] schedule, it’s like missing two days in another schedule. When they miss, it’s a lot of [catch-up] work.”

A change to the schedule, then, may actually benefit the students in more ways than just offering them the opportunity for more sleep.